The Wanga Kingdoms of Western Kenya: A forgotten betrayal, a living call for reparations

By Eunice Odhiambo, Reparations Officer – Africans Rising

When we speak of reparations for Africa, the conversation often drifts toward the transatlantic slave trade or the brutalities of colonial plantations. The story of the Wanga Kingdom in Western Kenya reminds us that colonial injustice was not only about stolen labour overseas, it was also about the deliberate dismantling of African states, cultures, and sovereignties.

The Wanga, of Western Kenya, were not a disorganized people waiting to be “civilized.” They had their own systems of governance, a spiritual order that guided succession, and a thriving economy. After the death of Nabongo Osundwa, following a succession battle between his sons, the kingdom divided into two centers of power: Wanga Mukulu and Wanga Emwalo. This rift was spiritual as much as political, rooted in sacred burial rituals that defined legitimate rule. The existence of dual thrones remains part of Wanga life today, a living reminder of an ancient sovereignty fractured but never erased.

The Wanga, of Western Kenya, were not a disorganized people waiting to be “civilized.” They had their own systems of governance, a spiritual order that guided succession, and a thriving economy. After the death of Nabongo Osundwa, following a succession battle between his sons, the kingdom divided into two centers of power: Wanga Mukulu and Wanga Emwalo. This rift was spiritual as much as political, rooted in sacred burial rituals that defined legitimate rule. The existence of dual thrones remains part of Wanga life today, a living reminder of an ancient sovereignty fractured but never erased.

Before European conquest, the Wanga engaged Arab traders who brought Islam, firearms, and cultural influences that shaped the kingdom. The very name “Mumias” comes from Kwa Mumia, a Arabic/Kiswahili nod to Nabongo Mumia under whose reign the town grew into a regional hub. Arab ties brought both protection and contradiction: on one hand, the kingdom’s sovereignty was shielded from slave raiders; on the other, Wanga warriors; armed through these networks were sometimes deployed to support raids on neighboring communities and capture slaves. This left the Wanga both respected and resented.

Then came the Europeans. Among the earliest intruders was Carl Peters, the infamous German colonizer whose ruthlessness earned him the nickname Mkono wa Damu (“Man with the Blood-Stained Hand”). Peters saw in the Wanga who already had an organized governance system, armed with guns and seemingly “civilized,” a strategic ally for extending German influence in East Africa. He exploited Wanga divisions and courted Nabongo Sakwa of the Wanga Mukulu Kingdom with gestures of friendship, only to advance imperial ambitions. His dealings intensified rivalries and set the stage for deeper European penetration. While Britain eventually outmaneuvered Germany and absorbed the Wanga kingdom into its sphere, Peters’ interference epitomized how external forces manipulated African sovereignties, weakening them from within before subjecting them to outright conquest.

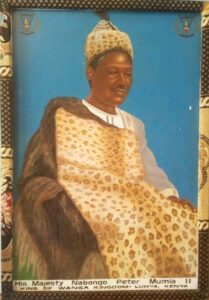

The British perfected this manipulation. They flattered Nabongo Mumia with the title of Paramount Chief of Kavirondo (modern day Western Region) under the British Crown, and his counterpart Wanga a local Chief but this was a calculated erasure of sovereignty. By 1926, Mumia was retired from authority altogether, his Bomani headquarters turned into a colonial administrative post. The throne was symbolically stripped bare.

The betrayal was multilayered. British officials did not hesitate to use Wanga warriors already armed and battle-tested to subdue neighboring peoples who resisted colonization. In this way, the kingdom that once stood proud was transformed into a tool for wider colonial conquest. Resentment deepened, and the Wanga’s coerced complicity further isolated them from their neighbors.

Religion was also weaponized. The killing of Bishop James Hannington in 1885 by Kabaka/King Mwanga of the Baganda Kingdom in present day Uganda was used to frame Africans as “savages” in need of salvation. Missionaries entered the Wanga kingdom under the banner of Christianity, dismantling shrines, demonizing ancestral practices, and replacing indigenous spirituality with foreign dogma. Four of Nabongo Mumia’s guards who had accompanied the bishop perished with him. The Anglican Church, hand in glove with colonial administrators, played a central role in eroding Wanga culture and justifying foreign domination.

The exploitation did not end there. During the two World Wars, thousands of Wanga men were conscripted into the King’s African Rifles. Livestock and grains were forcefully seized from households to feed the solders. Many were coerced or deceived with promises of pensions and land that never came. They marched and fought under brutal conditions, facing racism even as they bled for an empire that had stolen their sovereignty. When they returned, they were discarded, impoverished veterans with no recognition.

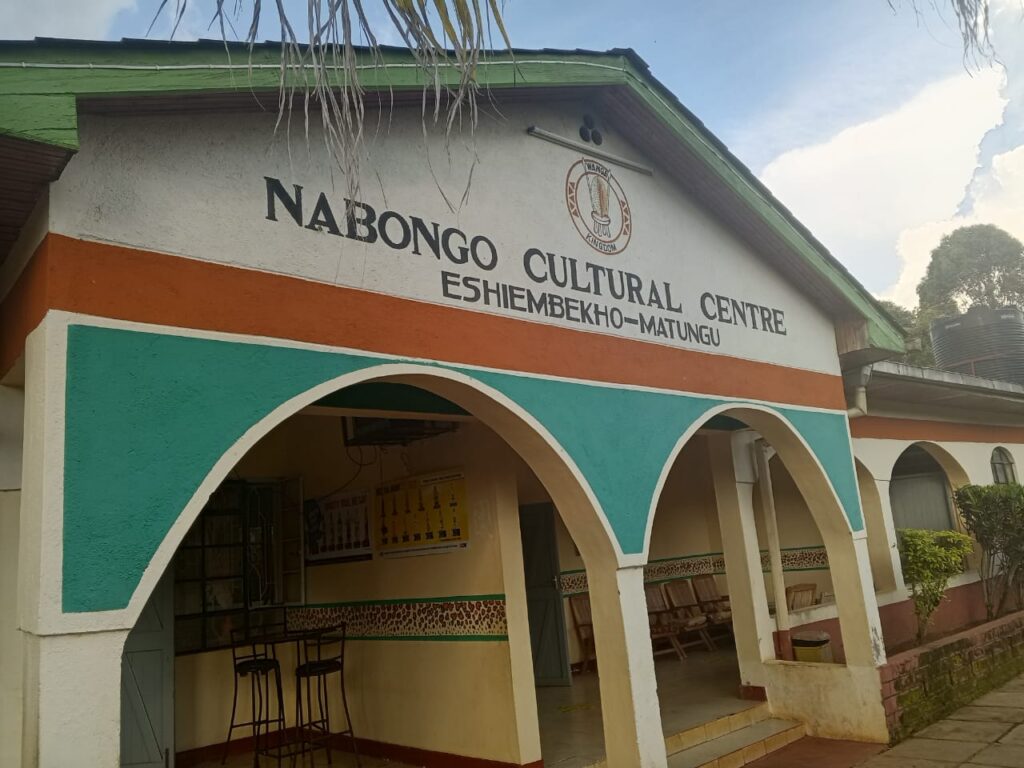

This is why reparations are not optional. They are a moral and historical debt. For the Wanga, reparations must mean more than money. They must include the restoration of cultural dignity, the return of regalia and sacred items, compensation for land alienation, recognition of veterans’ sacrifices, and an official apology from both the British state and the Anglican Church.

The Wanga story is not a footnote. It is a mirror. It shows us how colonialism worked through division, manipulation, and betrayal and why Africa’s demand for reparations cannot be silenced. The kingdom may have been diminished, but its call for justice endures. And in that call lies the unfinished business of decolonization.